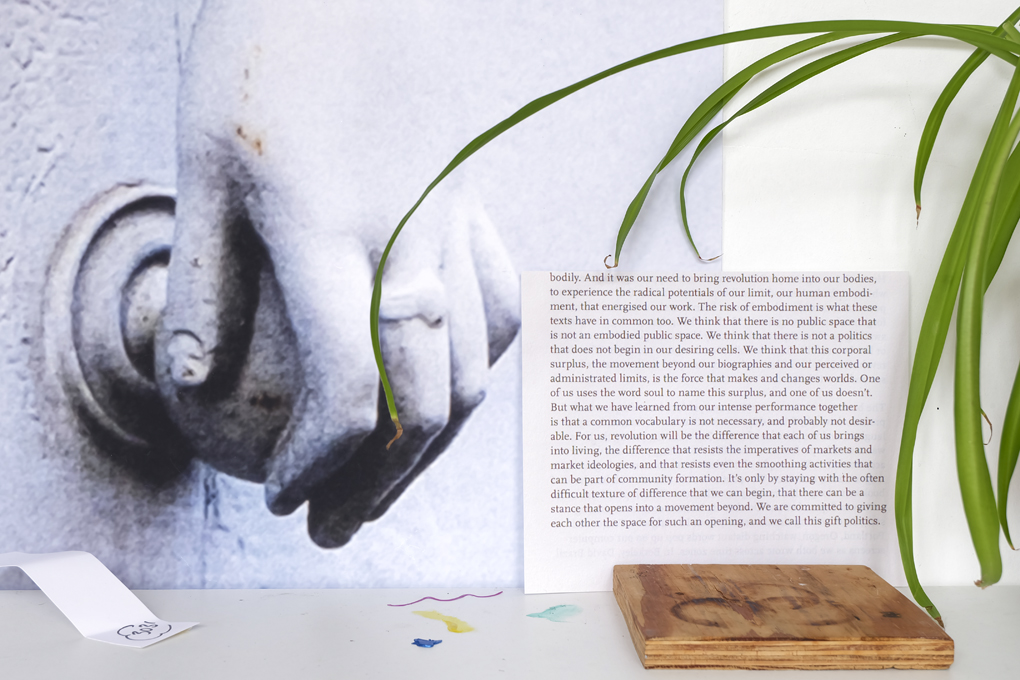

Print on Semi transparent curtain, rod, metal rings, 195 x 292,5 cm

Fine art print, framed in glassless wooden frame, 45 x 30 cm

Fine art print, framed in glassless wooden frame, 45 x 67,60 cm

Print on Semi transparent curtain, rod, metal rings, 195 x 292,5 cm

C-print on aluminium, 80 x 120 cm

Duratrans, Lightbox, 75 x 50 cm

With a background in sculpture, in which she created confusion as to what was art, means of display or entourage, Marije de Wit turned to photography in recent years. She protests against the tendency in which quantifiability, objectivity, and justification have come to dominate in life; art included. Still life-like photos of situations in the studio allow her to bring attention back to the artist and the work, claim space for subjectivity and ambiguity, and make way for things to exist and be valid before they meet their explanation.

The exhibition takes its title from the essay Browser art by Eileen Myles* . At its start, the essay is about the political in Wolfgang Tillmans' work, and specifically about a piece of text in one of his exhibitions: it talks about how there's still cultures that take pride in their modernism and freedom, but have difficulty with homosexuality nonetheless. Seemingly unrelated, Myles then goes on to talk about Imi Knoebel, who once described how during the bombing of Dresden, the flashes of bombs filled a triangular shaped window in the room of the attic he was in, and how the experience contributed to his love of simple shapes. Myles asks whether that is 'love, or merely imprinting'. (Gay-) emancipation and a visual experience of war both unite with art here. It shows that there are no distinctions between art and social change, or between abstraction and daily life.

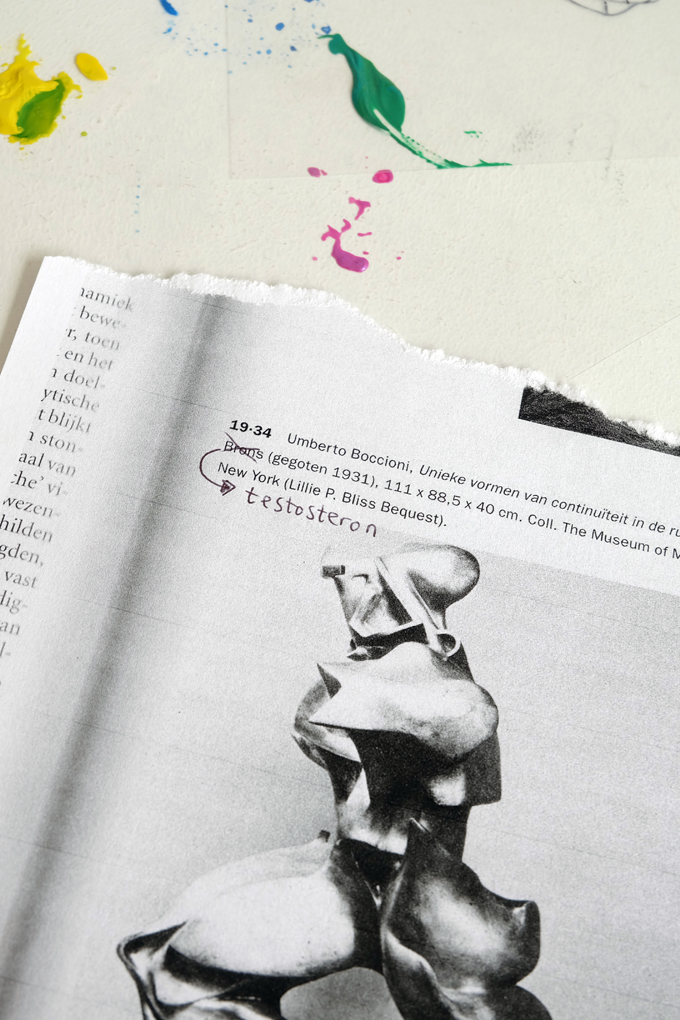

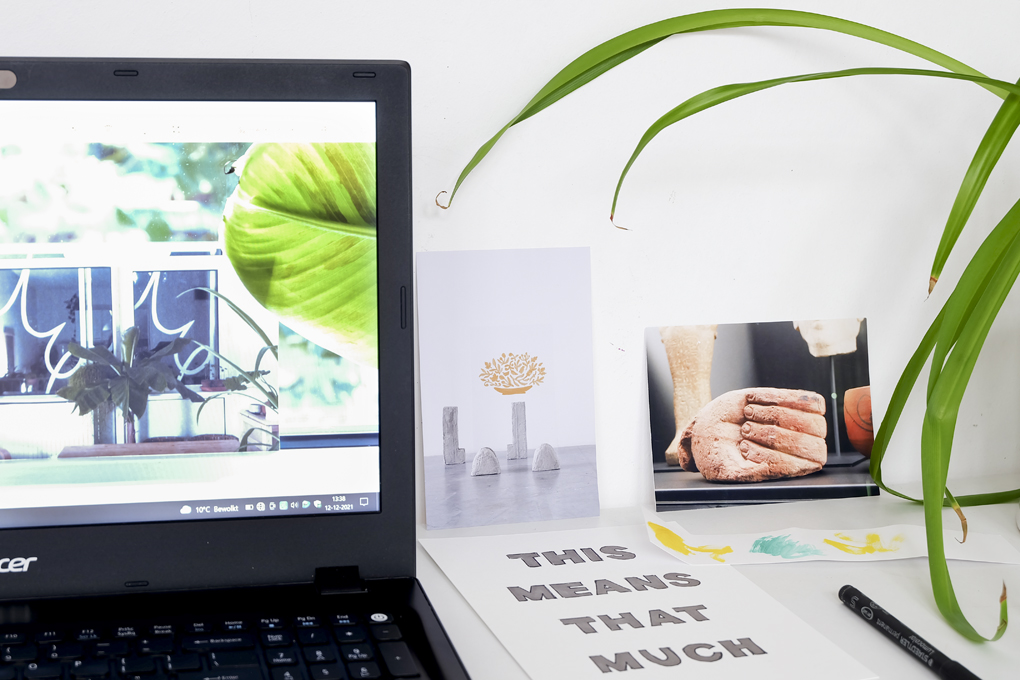

Dissolving distinctions between so-called opposites is precisely what Marije de Wit aims with this exhibition. Her photos show what the artist surrounds herself with in the studio: found and self-made imagery, found and self-written text fragments, and plants. Just like the plants appear as cuttings and as the forms they've grown into in later stages of their evolving existence, the images also recur in the different appearances they've had at different moments. Photos of bodies and body parts, sometimes as portraits, and sometimes in the form of sculptures, appear throughout the exhibition and alert us to our physical existence. Some represent moments in art history: they visualise what is seen and unseen in that history, and throw doubt upon the motives that are usually taught to have shaped it.

Together with a text fragment about the relation of the body to revolution**, shown on a photo that is made in to a curtain, these photos point out how we exist out of our physical being, and worlds of ideas equally.

Other text fragments represent De Wit's wish to not have to be linearly communicative in art. Where photography dissolves the distinction between making and finding, the total of these photos dissolve those between stating and questioning, subject and object, our physical and spiritual existence, and art politics and social politics.

* The Importance of Being Iceland, Eileen Myles, Semiotext(e), 2009

**Revolution: a Reader, Lisa Robertson, Matthew Stadler, Paraguay press, 2012

/

The Body, The Plane, The Camera | Article by Marianna Maruyama

Now More Than Ever | Publisher: WIELS, Brussels & Motto Books, Berlin

ISBN: 978-90-789372-9-6